In Ohio, many farmers employ a cropping system known as no-till. The benefits are many as much valuable time is saved from not having to till or plow the soil every spring as the former traditional method. Then too, valuable topsoil is not disturbed exposing it to erosion from wind and rain.

The no-till method of farming has been made possible with the Monsanto Company’s creation of glypsophate (Roundup) that has been very effective in use as a preplant irradicant of noxious weeds in fields and in later years as Monsanto has developed soybeans and then corn resistant to glypsophate, so that post control is possible after the crop seed has germinated and in later stages of the crop’s development.

The no-till method of farming has been made possible with the Monsanto Company’s creation of glypsophate (Roundup) that has been very effective in use as a preplant irradicant of noxious weeds in fields and in later years as Monsanto has developed soybeans and then corn resistant to glypsophate, so that post control is possible after the crop seed has germinated and in later stages of the crop’s development.

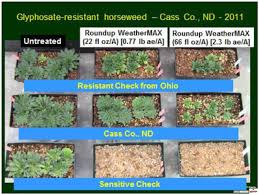

Glypsophate has been favored also because of its low toxicity to humans, fish and wildlife as well as adhering to the soil making water contamination unlikely. The glypsophate-no-till system had been the perfect solution until 2006 when a resistant population of a weed known as marestail (Conyza canadensis) started to appear in Ohio and Indiana.

Today the glypsophate-resistant strain is so prevalent it cannot be controlled alone with glypsophate as before. Unfortunately, marestail seed germinates in the fall when they are normally dispersed but the seed will germinate also the following spring and into summer. One plant of this noxious weed can grow from what is known as the short rosette stage in early spring to bolting to six feet or more by mid to late summer. After the plant blooms in late summer, seeds that are formed and that can number up to 200,000 are easily scattered by the wind. Seeds that germinate in fall have a 50 to 90% survival rate of the resulting seedlings infesting the crop land for the spring planting season.

Studies at Ohio State University have revealed a significant reduction in crop yields as the marestail weed competes with the crop for nutrients, water and even sunlight as the weed bolts in spring from from its rosette stage.

Tilling or plowing is effective prior to planting in eliminating the winter survivors in the spring of the weed but will not give control of the later germination of the widely distributed seeds.

The best method of a marestail control in Ohio is to do a “burn down” of the weed in fall or early spring to be followed with a pre-emergent weed control that will give an eight week or longer period of control of later germinating seeds.

After the effects of the pre-emergent control of marestail are no more, heavy crop canopies, especially of soybeans, will mostly keep the weed’s growth in check.

Again, a good strategy to control marestail is an initial burndown of the winter survivors in spring while the plants are small in what is known as the rosette stage.

For early spring 2,4-D or dicamba is good to use as a base herbicide combined with a reduced rate of a pre-emergent herbicide such as Canopy® or Cloak with the remainder of the residual herbicide applied closer to planting.

The “burn-down” application containing 2,4 D-ester and dicamba requires some training to apply as wind drift can damage or kill desirable plants around the field perimeter and cause problems as the spray drift travels onto neighbor’s property.

Burn down applications need to be applied as early as possible as higher rates of Dicamba will require at least one inch of accumulated rainfall and a minimum waiting period of at least 28 days before planting commencement.

Products for residual control include the trade names of Sencor, Valor,Gangster and FirstRate and Python.

The initial early spring “burn down” and pre-emergent control strategy is primarily used for soybeans for control of the now glypsophate-resistant strain of marestail.

No doubt, this native prolific weed will mutate so that today’s controls will no longer be effective. Science must evolve to counteract this threat to crop yields along with other weeds now becoming resistant to a variety of controls.

It will be interesting to see what the future holds as herbicide-resistant weeds continue to evolve.